One Hundred Years of Solitude, or an ode to the book that keeps on giving

Cease, cows, life is short! A love letter to (one of) my favourite book(s).

Just to be clear, this is very far from a plot summary or a comprehensive or even cohesive analysis of the novel. I am still sane enough to know I am unable to do that in a way that would be worth anyone’s effort but it is also not my intention at all at this point in time. Upon my (yet another) read of the book I simply want to finally put into words what it means to me, and tell you a bit more about how it came to be such a central part of my reading life. As it says in the subtitle, it’s a love letter, and those tend to be messy and a touch all over the place and full of personal connections to the addressee rather than a straightforward text with a clear structure.

For eight years now (nearly a third of my life), when met with the question of what my favourite book is, the answer that most immediately flows up to the surface of my mind is One Hundred Years of Solitude. I first read it when I was 16, my most advanced read in English up until that point, and I distinctly remember that it took me three months to finish. I kept picking it up as much as I could, at the end of long school days when I could barely keep my eyes open or string a cohesive thought, but something in that book kept drawing me in despite its complicated and confusing storylines which jump through time and leave you wondering if you just like some of the people in the story itself are losing your mind. I also had to refer to the family tree at the front of the book every few pages all the way till the very end to make sure I was not confusing characters from different generations and had the correct Aureliano or Jose Arcadio in mind for the scene I was reading about. Although, in my defence, quite a few characters themselves do precisely that in their delirious solitudes and old age made worse by the stabs of nostalgia, so I think anyone making the journey through One Hundred Years of Solitude should be absolved from occasionally making the same mistake.

Three whole months, from January to March. It was a labour of love, at times frustrating how slowly I was ploughing through it yet it caused something in me to irreversibly change, my perception of the what prose could do to one’s emotional landscape and outlook on family life was forever altered even if at the time all I could process was that I had truly thrown myself into the deep end and was in a territory of literature I had not even conceived could exist. Very few books I had read had until then had managed to completely engulf me to the point of forgetting to eat or drink, and I have to give them credit for being the reason I thought myself ready to tackle something as monumental as One Hundred Years of Solitude (shoutout to The Secret Garden, The Children of Captain Grant, and a few middle grade Bulgarian books which I hope to see translated one day). Or maybe it was pure naivety and lack of familiarity with the task I was setting for myself. It was both.

Marquez’s talent to seamlessly blend magical incidents with real life circumstances and combine five different tenses in a couple lines solidified my love for longwinded sentences that make you involuntarily hold your breath and leave you feeling like you too are suspended in the air (as certain characters do, if you know you know). I do not enjoy stories with short punchy sentences at their foundation at all, unless they sound like this: “Cease, cows, life is short!“

Marquez does this thing where by the end of the book the strange and the impossible and the unexplainable have become so delicately interwoven into the tapestry of the storyline and perfectly mixed with the realistic that when someone is said to be telepathically communicating with a bunch of doctors or when animals reproduce at a naturally inconceivable pace you don’t dwell on it too much and simply accept it as fact. At 16, I was absolutely enthralled by his style and ability to build such a rich and lively world which upon entering always felt like a strange alternative reality I had found a secret door to by accident. Even after my third journey through the (over) hundred years of Macondo’s (the name of the town in the book) existence I still feel that if tasked I would fail to recall most of what happens to many of its inhabitants because those 400-something pages are so richly saturated with everything from multiple wars and loud and lavish parties to unlikely companionships and even marriages and postponed or untimely deaths. People’s lives are inextricably connected to the lives of everyone else, both dead or alive, or somewhere in the middle; time goes around in circles with certain days and events stuck on repeat; characters’ traits mirror each other through the generations so closely yet are never quite exactly the same; characters you might have thought of as long gone suddenly make an appearance once again to prove you that you never could anticipate what reality is within Marquez’s story. And it all somehow makes sense, most of the time at least.

The second time I read it was towards the end of winter, in early 2020, as a way of distracting myself from the stress of my final semester at university but it ended up distracting me from the pandemic that hit instead. A book about solitude and nostalgia became my comfort read during a time when solitude was the world’s most widely shared condition. I appreciate the irony of it now. Once again, I loved it. Getting to read bits of the story every evening right before sleep became my little nighttime treat to myself, escaping from the catastrophes playing out in the world I inhabit and slipping into the ones faced by the inhabitants of those beloved pages. However, I think I was a bit too preoccupied with trying to survive living with my family again in closed quarters and finish my degree to pay it the attention it deserves, and instead just bathed in its glorious prose and fantastical scenes without diving too deep underneath the surface.

I have spent the last several years indulging in the fact that in London bookshops are everywhere, both charity ones where copies of most books go for £2 to £3 and ones with multiple floors stocking every genre conceivable; I have passed hundreds of my hours browsing shelves and consuming a lot of book-related content on the good old internet; I even worked in a bookshop for a couple months last year, constantly hoping someone would bring a copy of it up to the till and I would ask them to be my new best friend (it did not happen, unfortunately). I have therefore awarded myself with a sort of an amateur literary degree, even if I still haven’t read many of “the classics“. Who can tell me anything if I have read One Hundred Years of Solitude three times? So naturally, this year felt like the right time to take it off the shelf again, deciding I was finally equipped with the necessary grasp of how to understand an author’s style, world-building techniques and ways of creating character arcs, and with the ability pay attention to underlying themes and carefully planted details.

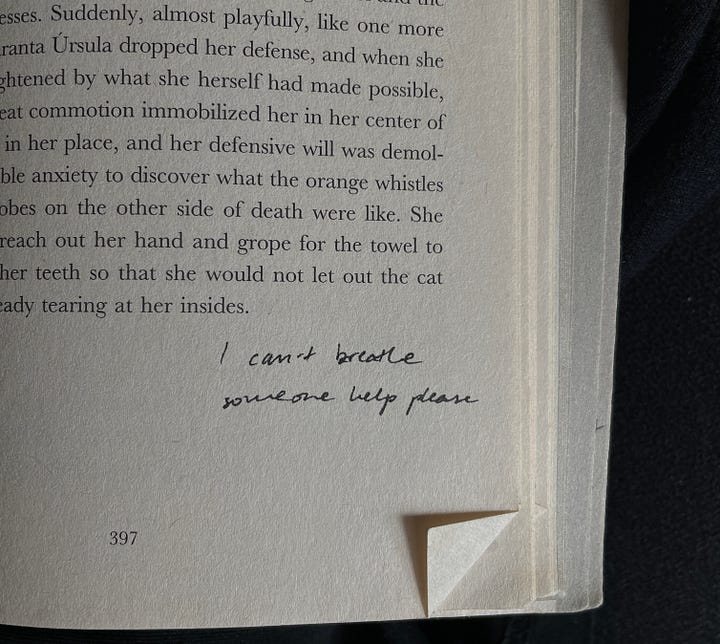

Similar to the previous two times, I took my time with it. I was consciously savouring the magic coming off its pages and refusing to rush through the chapters even though reaching the very last page with its absolutely brilliant finale where suddenly all the insofar ambiguous pieces of the puzzle finally fit together always feels like a triumph and sprinting towards it is a constant temptation. I even ordered myself a second copy, one clearly quite well read and very floppy with the clear intention of underlining and scribbling my thoughts in the empty spaces around paragraphs in pen, not pencil, permanently capturing my immediate thoughts and dog-earing pages I wanted to come back to. The first one that I own, the edition with the girl and the parrot on the cover which I dearly love for many sentimental reasons seemed too precious for me to “destroy“ in such a way. So its non-identical twin got to be the one that saw me clenching various pens in my mouth day after day and was the one that got shoved down bags and occasionally dropped from tables and thrown around on patchy grass in different parks across the city, the crumbs from many pastries stuck in its creases. It became my trusty companion for about three weeks, coming with me to run errands and try new cafes and return to old favourite ones, its pages propped open on various surfaces of varying degrees of stickiness, come rain or shine. It feels strange to be referring to a book in a way as if it’s a living and breathing thing that kept me company but it did, and I know enough people out there know exactly what I mean.

But mostly it was the characters living in the story that were always with me, one or two constantly at the forefront of my mind with their never-ending ails and sources of misery or contentment. As someone who intentionally spends a lot of time by themself and often finds great comfort in it, whenever the scales do go off balance and the feeling of solitude floods the system I do wonder what is it that I am gaining from this inclination to exist almost entirely by myself? And maybe that is one of the reasons why I adore One Hundred Years of Solitude to the extent to which I do because everyone in it is befallen by this very human experience, and seeing how they all adapt to it is a source of great curiosity to me. One cannot read and not wonder why do they desire solitude? Some of them purposefully seek it and make it the centrefold of their existence, the marker of their life, shutting off the outside world to their inner life sooner or later, or refusing to break the hereditary cycle if presented with the opportunity. The others simply accept it once it takes over their life, not bothering to change anything or find ways to survive the downward spiral it takes them on, or deliberately choose to be infected by it when entering into the life of any Buendía family member. Many of them seem to have made their peace with it by the time they are barely aware of their own consciousness, having accepted how their life would play out even if missing huge chunks of information on how or why they came to be. The presence of solitude in their very core is the one thing they know is certain about who they are. No matter how far they stray from home and their family it is there trailing behind them, following them around like a second shadow.

However, I am not here to summarise the plot (which is a near impossible and arguably counterproductive task) or delve deeply into characters’ actions and reactions and life choices. There are so many things that take place between the opening and the closing sentences that those 400 pages often feel like four thousand instead. It’s an exercise in perseverance and a test of your patience but the rewards along the way more than make up for it. The prose is hands down one of the most awe-inspiring things I have ever had the pleasure of familiarising myself with, and the way the story flows so effortlessly even when at its messiest is undoubtedly something to marvel at. Exhibit A of many:

Frightened by the passion of that outburst, Amaranta Ursula was closing her fingers, contracting them like a shellfish until her wounded hand, free of all pain and any vestige of pity, was converted into a knot of emeralds and topazes and stony and unfeeling bones.

I am more than aware that it is a rather polarising body of work due to the arguably high number of (spoiler alert) near incestuous incidents, and for many readers the levels of symbolism and mystical references can be overpowering and distract from the ‘main storyline‘. Yet there isn’t really a main storyline, is there? One can definitely find at least a handful of ways in which to interpret what goes on in the book, depending on what you focus on. There is the political aspect of the novel and the heavily present theme of war, Liberals and Conservatives and rebels of all kinds always up in arms; the subject of colonisation and lack of commercial progress which when it finally arrives destroys the town’s life way more than it benefits it; the theme of a matriarchal hierarchy and the many strong-willed women who run the Buendía house and are respected members of the community, not afraid to put their foot down whenever needed and save the day. Every time you read it you can find a different way to untangle Marquez’s text. Everything that happens between the alpha and the omega, from Macondo’s founding to the final and full deciphering of those infamous scrolls, can be seen as open-ended. Because even when characters die they don’t really go away, their ghosts and presence always looming in the corners of houses, haunting anyone who would pay them attention, their legacies sooner or later picked up again by one of their successors. Time is anything but linear in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

"It's all right, child," she consoled him. "Now tell me who it is."

When Aureliano told her, Pilar Ternera let out a deep laugh, the old expansive laugh that ended up as a cooing of doves. There was no mystery in the heart of a Buendia that was impenetrable for her because a century of cards and experience had taught her that the history of the family was a machine with unavoidable repetitions, a turning wheel that would have gone on spilling into eternity were it not for the progressive and irremediable wearing of the axle.

It is also an excellent source of nearly endless character study, the omniscient narrator knowing everyone’s feelings and thoughts at all times. Which, considering the incredibly long list of characters followed in the novel, can and does get overwhelming, as many critics have stated over the years ever since the book was first published. Being able to get inside so many different people’s minds and see the different but always equally affecting ways in which solitude settles into their bones is a lot for a reader to take in even on a good day. No wonder it takes a few thorough reads to start being able to put yourself at a healthy distance from their unending pain and forms of insanity and obsession, and appreciate and laugh at the exaggerations and irrational scenes rather than scoffing at their incredulity.

Similar to many real life families and the people in their immediate vicinity, the characters in the novel are defined by each other. They all lead very different lives but are always, whether they like or embrace it or not, tied psychologically to the others of the same last name. Members of the Buendía family are all born with the same predisposition to overpowering solitude and are prone to great bouts of nostalgia, which ironically does not bring them together at any point; they all live with it in their own way and find ways to mould it into something strictly individual. It’s a hereditary trait that they seem to get recognised for immediately, just like it happens to many of us when someone who knows our parents looks at us, though I imagine it would be a rather strange feeling to be recognised for the solitude apparent in your eyes and the way your carry yourself rather than for the colour of your hair or shape of your nose.

That drawing closer together of two solitary people of the same blood was far from friendship, but it did allow them both to bear up better under the unfathomable solitude that separated and united them at the same time.

The more I read it and think about it the more reasons I find to love it. But as time passes some begin to extend beyond the book. It’s a marker I use to measure against how I have grown both as a person and as a reader. Discovering something that you find just as compelling today as when you were 16 and continue to find bits to take away from every time you revisit is such a precious feeling. Being able to continuously connect with a piece of literature throughout very different stages of your life is where the magic of reading lies in. I will absolutely never ever shut up about this book, and will continue to point at it whenever I am in a bookshop with someone and tell them that they must read it if they want to remain friends with me. It has become my signature book gift too, it is the most ‘me’ mark I could for being in someone’s house or life, and several of my friends now have it on their shelves as a result. And if you are someone who has read it because of me, I love you, even if you did not necessarily discover a new all time favourite and perhaps even questioned my sanity, I don’t care. <3